Abstract

This blog unpacks how the opioid crisis in Philadelphia, with a heavy focus on Kensington, is socially constructed through the city’s historical, deeply-rooted, structural inequalities resulting from the consequence of redlining, racial segregation, deindustrialization, and political disinvestment. This blog, through the use of research methods from social epidemiology and medical anthropology, argues that death by overdose and health disparities can be traced to those neighborhoods that have been historically left behind and redlined. The idea of structural violence sees addiction not as a moral failure of a person but rather as the result of discriminatory policies which have been determining the conditions of the neighborhood for many generations.

Keywords

redlining, structural violence, Kensington, opioid overdose

Redlining: How History Shaped Philadelphia’s Opioid Crisis

It is impossible to fathom the extremity of the opioid crisis in the Kensington area of Philadelphia based only on an individual level, as socioeconomic factors play just as big a role in shaping Kensington to be the way it is today. The result of the alteration of racial housing segregation, racial police harassment, and racial disadvantage has demonstrated how the circumstances of Kensington today are not the outcomes of mere chance, but rather as a result of policymakers’ choices since the 1960s, who have abandoned certain areas to suffer most from the cycles of addiction, violence, and death.

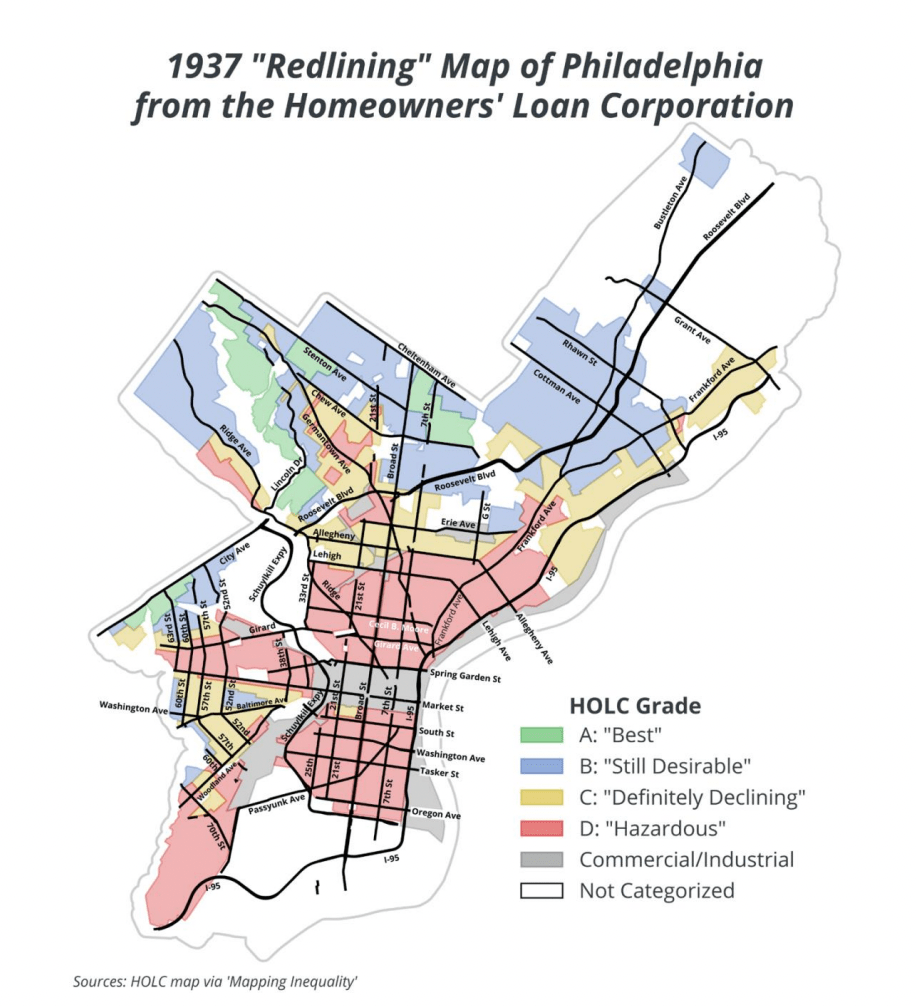

One of the historical causes of opioid use is redlining, a mid-century real estate policy targeted to separate districts according to racially biased criteria. Kensington, along with many other predominantly Black, immigrant, and working-class districts were deliberately labeled “hazardous” by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), and as a result had to endure denial of access to loans to the homes in the inner-cities of the Philadelphia area, Lower Merion, Abington, and also Whitman Park.

To explore more about HOLC and the history behind redlining in New Deal America, visit Mapping Inequality or click the button below.

Figure 1. 1937 “Redlining” Map of Philadelphia from the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation

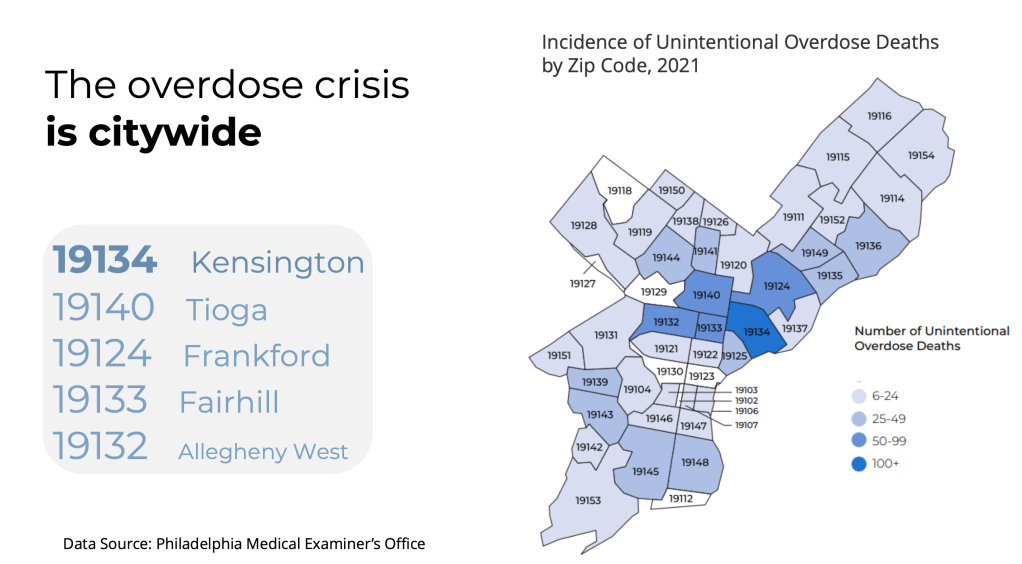

Figure 2. Incidence of Unintentional Overdose Deaths by Zip Code, 2021.

As a result of segregated communities, where there is a lack of financial resources, today we see even more concentrated areas of poverty. Historical redline as shown in Figure 1 shows a direct correlation to the rate of overdose in the Philadelphia region today, as shown in Figure 2, with the highest concentration overdose death in Kensington.

For a while, the city center of Philadelphia was the core of American industrial economy consisting of the clothing industry in Camden and metalworking of Kensington. However, in the 1950s to 1960s, America faced a large-scale shutdown of these manufacturing plants, resulting in a major economic shift as lots started vacating and buildings shut down. This decline led to several consequences, including:

- Significant job losses for both blue-collar and white-collar workers

- Widespread economic decline and significant population loss in affected neighborhoods like Kensington

- Abandoned factories and housing, leading to cycles of poverty, increased crime, and drug problems.

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health reveal that the rise in deaths due to drug overdoses is situated mainly along the Kensington corridor with very few cases in the well-to-do neighborhoods of Center City and Chestnut Hill. Hence the location phenomena of Nancy Krieger’s eco-social theory become visible: people being biological “embodiments” of societal inequality. The situation in Kensington mirrors the theory in the aspect that multifactorial discrimination in housing, racial segregation, pollution, in addition to other strained difficulties has resulted in a high level of substance abuse and early deaths over time.

The law enforcement system in Philadelphia does not helping to alleviate the issues that the historical effects of redlining leaves behind, but rather intensifies them. In addition to socioeconomic discriminations that residents and visitors in the area of Kensington face, they also experience polic brutality, with a lock of social and community services. Law enforcement and media often blame the neighborhood’s “open-air drug market” as the reason for heightened patrolling, but in reality, no sustainable action has been taken to provide residents who suffer with drug addiction real stability, in turn, avoiding the issue of community intervention. This is yet another example of structural violence, which demonstrates how state interventions aggravate already existing problems by criminalizing residents who suffer from drug addiction rather than solving the root of the issue.

By going through these steps we understand the drug problem in the area of Kensington revolves around the structural components created over the years which led to a situation where not only addiction could arise but also perpetuate. Therefore, any policy intervention must first deal with that history instead of only tackling the symptoms. There is a reason why history exists: it shows us not only what happened in the past, but also teaches us how to avoid the same mistakes in order to create a better present and future.

Leave a comment